Applying Fusion to ZK: Nearly 2× Performance Improvement Over ICICLE

As introduced in TensorFlow XLA: The Fusion Compiler for TensorFlow, one of XLA's most important optimizations is Fusion. This article will briefly discuss what Fusion is, why it's crucial, and the actual performance benefits of applying it in the context of ZK.

What is Fusion?

Loop Fusion, for example, means combining loops like the following:

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

d[i] = c[i] * a[i];

}

Into a single, fused loop:

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = (a[i] + b[i]) * a[i];

}

In compilers like ZKX, operations like element-wise operations are primary candidates for fusion.

For example, consider the following HLO-like operations:

ENTRY %main {

%x = parameter(0)

%y = parameter(1)

%0 = babybear[n] add(%x, %y)

ROOT %1 = babybear[n] multiply(%0, %a)

}

Through fusion, these operations are combined into a single one, as shown below:

%f {

%x = parameter(0)

%y = parameter(1)

%0 = babybear[n] add(%x, %y)

ROOT %1 = babybear[n] multiply(%0, %a)

}

ENTRY %main {

%x = parameter(0)

%y = parameter(1)

%0 = babybear[n] fusion(%x, %y), kind=kLoop, calls=%f

}

So, let's explore why combining operations is so important.

Why Fusion is Important?

The problem we are tackling is memory-bound, so we must exploit the memory hierarchy to optimize memory transfers.

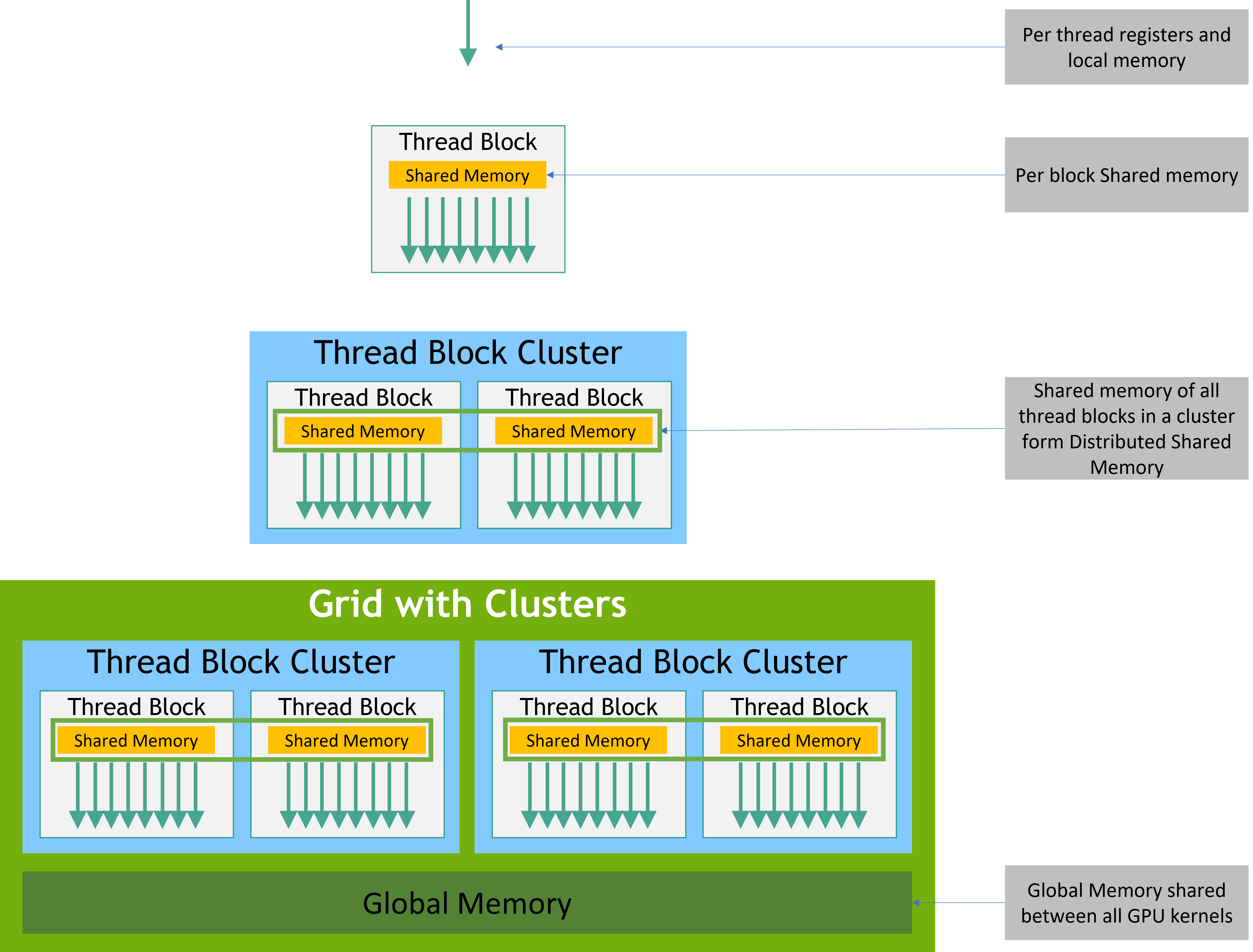

You can think of GPU data movement in three tiers. The lower you go, the faster and smaller it gets:

- Host ↔ Device transfers: PCIe/NVLink, etc. The most expensive (high latency, limited bandwidth).

- Device Global Memory accesses: high bandwidth but off-chip, so latency is still large.

- On-chip resources: L2/L1, Shared Memory, registers. Fastest.

The key principle: minimize round-trips in (1) and (2) and stay in (3) as long as possible.

When do Host ↔ Device transfers happen?

Whenever we copy data from the host to the GPU (e.g., using cudaMemcpy or Unified Memory migration) — or in the reverse direction — we incur expensive host-device transfers.

When do Global Memory accesses happen?

To share data across kernel boundaries, intermediates must be written to Global Memory and then read back by the next kernel. This quickly accumulates cost.

Once a kernel is launched, computation is distributed over Grid / Block / Thread. Within a kernel, Shared Memory and Caches handle local sharing. But if temporal or spatial locality is broken, Global round-trips become costly.

Revisiting Our Example

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

d[i] = c[i] * a[i];

}

Let's assume each loop is launched as a separate GPU kernel. Then two problems arise:

- Two separate kernel launches are required.

- The intermediate array

cmust be written to Global Memory so that the next kernel can read it back to computed.

Now, let's look at the fused version again:

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = (a[i] + b[i]) * a[i];

}

If we apply fusion, both of the problems above are solved. This is a critical optimization because this computational pattern (a sequence of element-wise operations) is extremely common in ZK, particularly in procedures like Sumcheck and Quotienting.

Benchmark Results

This principle seems simple, but it often breaks down when using frameworks like ICICLE for GPU programming. This is because each vector operation (vecop) is typically a separate kernel call, as seen in their API documentation.

We ran a benchmark for the operation (where ) on an RTX 5090:

| k | ZKX (ms) | ICICLE (ms) | ICICLE / ZKX |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 10.86 | 17.11 | 1.57× |

| 21 | 21.40 | 35.33 | 1.65× |

| 22 | 41.49 | 71.90 | 1.73× |

| 23 | 81.81 | 143.85 | 1.76× |

| 24 | 160.61 | 288.03 | 1.79× |

| 25 | 320.26 | 582.06 | 1.82× |

The results showed a 1.5-2× performance improvement between the fused (ZKX) and unfused (ICICLE) versions.

Performance Analysis

As the problem size grows (increasing ), the performance gap widens:

- At (1M elements): 1.57× speedup

- At (32M elements): 1.82× speedup

This trend demonstrates that fusion becomes more critical as problem sizes increase, which is exactly the regime where ZK proving operates.

Why Manual Fusion Isn't Enough

To be fair, the ICICLE team is aware of fusion's importance and provides a way for users to manually apply fusion using their program API.

However, this manual approach only scratches the surface of what a compiler can automate. Expecting users to:

- Understand intricate hardware architecture details

- Manually handle the full suite of loop optimizations such as Tiling, Vectorization, Loop Unrolling or Software Pipelining

...is an extremely difficult and unreasonable burden. This is precisely the work a compiler should do.

Compiler-Driven Optimization

The compiler automatically identifies fusion opportunities by analyzing the computation graph.

Multiple kernels are automatically fused into a single kernel, eliminating intermediate memory operations.

Fusion is just one of many optimizations. The compiler can compose:

- Constant folding

- Algebraic simplification

- Memory layout optimization

- Additional loop optimizations

...in ways that manual optimization cannot practically achieve.

Conclusion

Fusion is a fundamental compiler optimization that becomes critical in memory-bound workloads like ZK proving. While manual fusion APIs provide some benefit, they:

- Require deep hardware expertise from users

- Don't compose well with other optimizations

Our benchmarks demonstrate 1.5-2× performance improvements over ICICLE simply by applying fusion, and this is just the beginning. As we continue to develop ZKX, we expect to achieve even greater speedups through the composition of multiple compiler optimizations.

The future of high-performance ZK proving isn't in hand-tuned GPU kernels — it's in sophisticated compilers that automatically generate optimal code for any hardware target.